The freelance dance industry is tough, and it’s crucial for dancers to cultivate mental toughness, including grit, resilience, and hardiness. However, there’s a prevalent belief that mental toughness equates to simply persevering through pain and exhaustion. ‘Messages about pain and rest that dancers are exposed to contribute to beliefs and behaviours that increase injury risk and impede recovery’ (1).

I will never forget about an audition I went to once with a company I respected. Within the first 15 mins for the 3 hour long audition they had killed us off with a gruelling High intensity workout to essentially weed out the weak. I pushed my self to the limit in that audition because I wanted the job and I knew how to recovoer appropriately after. However this ‘think like and athlete’ mindset can do more harm than good if it perpetuates a culture that demand an extremely high tolerance for pain, and art at the expense of personal wellbeing.

We may feel that in this climate we can't afford to take time off. If we let on that we are injured or tired or just need a break from dance then others may perceive us as unreliable or lacking commitment. (2)

This mindset can rob freelance dancers of the joy they once found in their art, leaving them feeling disconnected, physically and emotionally exhausted, and guilty for resting. It may lead to avoidance of classes and auditions due to fear of not meeting expectations, compounded by physical signs like injuries and a feeling of unworthiness when it comes to success.

If this resonates with you, keep reading. I’ll guide you step by step through ways to overcome these challenges and reclaim your joy and inspiration for dance.

Why are we so hard on ourselves?

Research shows that variables relating to athlete burnout include pressure to perform, a competitive environment, heavy training demands, sport specialisation, and societal pressure (3, 4, 5). Perhaps you grew up in a demanding dance environment where any failure reflected poorly on you—where failure was simply not tolerated. Maybe you often found yourself comparing your progress to that of other dancers in your class, fuelling your desire to push harder.

Indeed, the freelance dance climate mirrors broader societal trends, accentuating competition. At times, it can feel as though we simply cannot afford to fail (6).

Perfectionism is a powerful force of motivation. Perfectionists can work hard and be determined and become successful! (7) Although often dance has a toxic culture of pain tolerance. There is a level of expectancy to just persevere and to push through. And we do it! Physical and emotional exhaustion are simply the norm. Many freelance dancers exhibit high levels of grit (8). However, reaching our dream goals and landing coveted jobs does not guarantee happiness or immunity from burnout once we get there.

There are various opinions and theories regarding the positive and negative aspects of perfectionism. Is the ‘good’ side of perfectionism truly about the pursuit of excellence, or are they different constructs altogether?

Regardless, to what extent does your pursuit of excellence detract from your sense of self and well-being? How can we identify maladaptive perfectionist tendencies that may be hindering our progress?

You may have standards that are far beyond what is realistically achievable. You might feel that you can never meet other people's expectations, or perhaps you believe that others will inevitably let you down by not meeting your high standards. These perfectionistic traits can lead to high levels of stress, anxiety, isolation, and potentially burnout (9).

Feeling stuck

I have worked with artists who wish to be less hard on themselves but are afraid that their standards will drop. Their self-criticism often leaves them feeling even less in control of their careers, and they continue to struggle with self-confidence as dancers and in how they look. Many dancers express frustration over feeling as though they are never doing enough, perpetually drained, and constantly comparing themselves to others while worrying about what others think of them.

The silver lining is that you can actively work to replace the pitfalls of perfectionism with tangible strategies for developing yourself as a dance artist, all without being overly critical of yourself.

How to take control

When you experience overwhelming frustration and the existential dread of being an artist, it places your whole being in threat mode.

‘This is crap, be better’

‘You’re better off not even trying’

You’re unhappy with your performance, you feel frustrated, I get it, let’s look into it.

Paint the Whole Picture

To understand your current situation, it’s essential to paint a complete picture of your reality. State the facts clearly: ‘This happened this way, at this time.’

Are you experiencing a creative block?

Are you feeling lost regarding where to focus your energy?

Do you feel isolated and uncertain about whom to speak to?

Is something not feeling right in your practice, but you're unsure what it is?

Reflecting on these questions can help clarify your thoughts and feelings.

Let’s Identify a Specific Emotion

This process will lead us to the root cause of your situation. Are you feeling frustration, anger, anxiety, shame, or disgust?

What Is the Root of It All?

Typically, the beliefs that cause critical or unhelpful thoughts are ingrained and often go undetected. They can linger subconsciously, repeatedly influencing our thoughts. However, we can bring awareness to these underlying beliefs.

We can essentially become our own detectives. Beliefs and fears are often found in statements such as:

‘If…then…’

If I take time off to rest, then I’ll lose my edge.

If I struggle with choreography, then I must not be a good dancer.

‘If I don’t…then…’

If I don’t push through this pain, then I’ll be seen as weak.

If I don’t constantly seek feedback, then I’ll never improve.

These beliefs are what dancers and I typically work on together in 1:1, as subconscious fears often require some digging to uncover and work through.

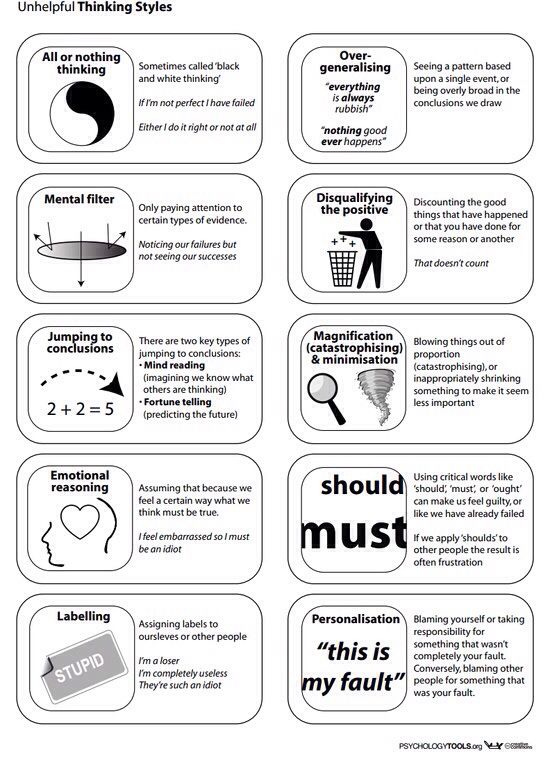

Unhelpful Thinking Styles

Sometimes, these beliefs and fears lead to assumptions and unhelpful thinking styles that are inaccurate and negatively biased.

(15)

You might feel that if you don’t keep working, you’ll never get ahead. Perhaps it seems that if you aren’t getting jobs or showing that you’re practising, you’re not really a dancer.

It’s entirely understandable to feel this way, given the current state of the freelance landscape. But you’ve taken a challenging step by being here. You’ve committed to supporting yourself through this difficult time. Try adopting the mindset of helping a friend or a younger sibling navigate their challenges rather than focusing solely on yourself.

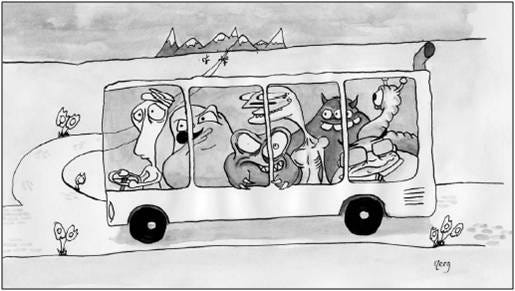

Diffuse from the Thoughts

It's difficult to challenge critical thoughts and judgments when we are overly identified with them. If you find yourself caught up in your thoughts, consider practising ‘defusion.’ This process involves noticing your thoughts and letting them go rather than getting entangled in them.

Like a bus driver ,you can be in the driving seat. All the passengers (thoughts) are noisily chattering, being critical or shouting out directions. You can allow them to shout, but you can keep your attention focused on the road ahead.

(13)

Judgments and critiques often distract us from reality, and they tend to feed unhelpful emotions such as anger, guilt, and shame.

Taking a Non-Judgmental Approach

This is where the challenging part comes in. You might notice resistance to what I’m about to share. I encourage you to embrace it. What’s the worst that can happen, right?

Taking a non-judgmental approach to unhelpful thinking styles can help balance your thoughts and rewire your beliefs.

Statements of Preference:

“I would like…”

“I prefer…”

“I wish…”

Statements of Consequence:

“This is helpful/harmful for…”

“This is effective/ineffective for…”

Reframing Examples:

“I am a failure” → “I am trying my best.”

“I’ve ruined everything” → “I am struggling with… but I’m doing well with…”

As I mentioned earlier, it can be challenging to pinpoint the rooted beliefs and fears when we feel overwhelmed by emotions and repetitive judgments and critiques of ourselves. I encourage you to regularly journal your experiences.

Challenge yourself to write a certain amount or for a specific duration each day for one week. I’ve been influenced by the book The Artist's Way, which encourages you to write three A4 pages daily for 84 days. (14) This might seem daunting at first, but you’ll find it interesting how quickly it becomes easier and how readily you can identify recurring thoughts and underlying beliefs.

The important part of journaling is to adopt a non-judgmental approach, allowing you to uncover new solutions and outcomes as you move forward. Beyond that, challenging our thoughts might not be enough to truly change how we feel. You may find it difficult to let go of worries and concerns and may feel stuck in old ways of working. To truly change how you feel, it’s essential to change your behaviours as well, not just your thoughts.

Changing our thoughts and behaviours isn’t easy, but with practice and persistence, we can learn more adaptive ways of thinking. If you want to improve your life as a freelance dance artist, embrace these practices; they can lead to profound changes in your personal and professional life.

References

Saigal, M. (2024). Nourishing Dance. Taylor & Francis.

Jacobs, C.L., Cassidy, J.D., Côté, P., Boyle, E., Ramel, E., Ammendolia, C., Hartvigsen, J. and Schwartz, I. (2017). Musculoskeletal Injury in Professional Dancers. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 27(2), pp.153–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/jsm.0000000000000314.

Cresswell, S. L., & Eklund, R. C. (2007). Athlete burnout: A longitudinal qualitative study. The Sport Psychologist, 21(1), 1-20.

Crocker, P. R. E., & Graham, T. R. (1995). Coping by competitive athletes with performance stress: Gender differences and relationships with affect. The Sport Psychologist, 9(3), 325-338.

Malina, R. M. (2010). Early sport specialization: Roots, effectiveness, risks. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 9(6), 364-371.

Wood, K. (2022). Freelance dance artists’ working ecology. In British Academy Innovation Fellowships Scheme. https://freelancedance.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/J5090-23_Karen-Wood-freelance-Fellowship-report_V5_FINAL_DIGITAL.pdf

The Sport Psych Show Podcast (2023). #146 Dr Andy P Hill - Perfectionism in Sport. [online] YouTube. Available at:

[Accessed 21 Oct. 2024].

Farrer, R. and Aujla, I. (2016). Understanding the Independent Dancer: Roles, Development and Success. Dance Research, 34(2), pp.202–219. doi:https://doi.org/10.3366/drs.2016.0159.

Hill, A.P. (2023). The Psychology of Perfectionism in Sport, Dance, and Exercise. Taylor & Francis.

Bennett-Levy, James. (2003). Mechanisms Of Change In Cognitive Therapy: The Case Of Automatic Thought Records And Behavioural Experiments. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 31. 261-277. 10.1017/S1352465803003035.

Veirs, K., Baldwin, jonathan D., Fagg, A.H., Haleem, A.M. and Dionne, C.P. (2021). Perrella Veirs-2021-Survey of Ballet Dance Ins. [online] 33(4), pp.226–233. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/369475335_Perrella_Veirs-2021-Survey_of_Ballet_Dance_Ins [Accessed 21 Oct. 2024].

Jowett, G.E., Mallinson, S.H. and Hill, A.P. (2016). An independent effects approach to perfectionism in sport, dance, and exercise. pp.101–165. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315661100-12.

Archer, R. (2013). (How to) Stay on The F*****G Bus. [online] Working with ACT. Available at: https://workingwithact.com/2013/03/17/how-to-stay-on-the-fg-bus/ [Accessed 21 Oct. 2024].

Cameron, J. (2020). The Artist’s Way. Souvenir Press.

Llc, S. K. (2017, February 10). Cognitive Distortions – Unhelpful Thinking Styles (Extended). Pinterest. https://uk.pinterest.com/pin/290200769725713912/